|

Wartime Winton - a child's view

by Pamela Lee (née Heath)

I was 5 years old when World War Two was declared — 7 weeks before my

6th birthday. We had moved house from Worthing along the south coast shortly

before this, because my father had been sent to the Westminster Bank in Winton,

a district of Bournemouth.

I remember sitting on the floor in the dining room

of our rented house in Winton with my two brothers — Cyril,

2-and-a-half years older than me, and David, 2-and-a-half years

younger. Something was wrong — it seemed rather dark and

rather quiet and we were affected by the tension in the house

and the way our parents seemed so serious. I think we had just

been given Arthur Mee's Children's Encyclopaedia, all 10 volumes,

and I have it still. Then our parents came quietly into the room

and my father told us very seriously that war had broken out.

Of course, we didn't really know what that meant, but they had

been teenagers in the First World War and my mother had lost 2

brothers. We soon found out.

My mother had to sign on for war work, but was signed

off again immediately because of her three young children. My

father was declared to be in a Reserved Occupation which meant

he didn't go away to war as the fathers of my friends did. He

worked in the Bank all day and spent the nights fire watching

in our road (up the church tower I think), or watching for enemy

aircraft on the cliffs with the Home Guard. He spent most of the

weekends with the Home Guard too, training and carrying out exercises

to prepare them to defend us in the event of an invasion.

The threat of invasion

The threat of invasion was very real and my mother

told me of a dreadful night while we were on holiday at Mill Farm

near Witchampton, about 10 miles from Bournemouth. I loved Mill

Farm, I could hear the rushing stream that used to turn the mill

as it flowed past my bedroom window and I got up at 6am every

day to 'help' the farmer milk the cows. I loved their warm breath

and the low mooings and the swish of the milk as the farmer squirted

it by hand into the bucket. I could sit on the little 3-legged

stool and watch him for hours. My mother had been a Land Girl

and learned to milk, so it must have been in my genes.

We still had our little Morris 8 car to drive to

the farm so it was very early in the war, before we had to lay

it up in the garage on bricks to keep the tyres off the ground,

because there was no petrol. During the night, she told me, they

heard that there had been an invasion, and we were only 10 miles

from the coast. My father and the farmer, and maybe other men,

stood outside the farmhouse in the dark with pitchforks and rabbit

guns, and my mother was instructed to wake us 3 children, put

us in the car and drive north, no matter that she didn't know

how to drive or where to go — this was life or death stuff.

Mercifully another message came through to say that it had been

a false alarm.

The early years of the war in Winton

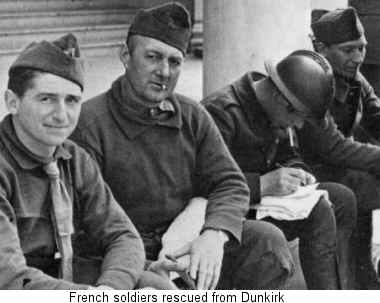

One

of the first things I remember is being astonished to find French

soldiers in their uniforms sitting on the

pavements. They were billeted in Alma Road School just around

the corner from where we lived. We were full of curiosity and

tried to talk to these strange beings - but without a lot of success.

They were kind to us and gave us dark brownish red and blue leather

notebooks, I think they had a pencil and a mirror in them. They

also said what sounded like 'Allivoozonk!' loudly and frequently.

We thought this was a wonderful word and chanted it back at them.

It was several years before I understood that they were saying

'Go away!' (Allez-vous en). One

of the first things I remember is being astonished to find French

soldiers in their uniforms sitting on the

pavements. They were billeted in Alma Road School just around

the corner from where we lived. We were full of curiosity and

tried to talk to these strange beings - but without a lot of success.

They were kind to us and gave us dark brownish red and blue leather

notebooks, I think they had a pencil and a mirror in them. They

also said what sounded like 'Allivoozonk!' loudly and frequently.

We thought this was a wonderful word and chanted it back at them.

It was several years before I understood that they were saying

'Go away!' (Allez-vous en).

My father, not content with looking after and drilling

his Home Guard Platoon also trained us. When we heard a bang we

had to fling ourselves on the floor and put our hands over the

back of our necks for protection. When we hear him shout 'Gas'

we had to put on our gas masks asap and not expect any help from

him. Then he would check that we had done it correctly, which

he did by putting a piece of loo paper on the bottom and making

us breathe in to keep it there. He had a whole gas chamber to

train the Home Guard in as well as us, but I will let my brother

David tell you about that as he remembers it better than I do.

My father also had a large map on the breakfast

room wall, just above my rocking horse. He listened intently to

the News on the wireless (we had to keep quiet then), and moved

little coloured pins on the map to show where the different battle

fronts were. We also had little notices on the wall by the electric

light switches and the hot taps. These had a rhyme on them: 'Switched

on switches and turned on taps, make happy Huns and joyful Japs'.

Some things were delivered by horse-drawn cart — maybe milk,

bread or coal. I ran straight out — there was no garden gate

as it was metal and had been taken away for the 'War Effort' —

to greet the horses which I loved. We also collected up what the

horses left behind with a dustpan and shovel for Daddy to put

on his allotment. As paper became more and more scarce we used

pieces of newspaper torn into squares and hung on a string in

the loo — I hated that.

My

father told us that the Germans dropped little devices in the

street which would explode when people picked them up. They were

disguised as bars of chocolate etc, and we were never to touch

them. My

father told us that the Germans dropped little devices in the

street which would explode when people picked them up. They were

disguised as bars of chocolate etc, and we were never to touch

them.

One day I was riding my bicycle to school and I

saw a match box lying in my path. I was convinced it was one of

these traps, so I thought I would cycle round the left of it,

then I changed my mind and tried to go round the right of it,

but in my fear I couldn't make up my mind and I cycled straight

over it, just having the presence of mind to lift my legs up in

the air and expecting it to explode. I was lucky — it was

just a match box!

We read the Dandy and the Beano and learned from

them that any strange person dressed in black and walking suspiciously

was likely to be 'Funf the Spy'. We giggled and pointed and whispered

'Look there's Funf' at quite a few lonely old people who answered

this description.

There were a lot of day time raids on Bournemouth

and at school we were always running downstairs to the basement

until the all clear sounded. We sometimes used to watch aeroplanes

fighting overhead — swooping down and climbing up again,

their engines roaring, and rat-a-tat-tatting with their machine

guns. One day we saw a Spitfire spinning down on fire. It crashed

on a house in Benellen Avenue, Bournemouth, demolishing it and

killing the pilot, who had not been able to bail out. We later

went to see the wreck — I wondered where the pilot was. We

also used to be taken to see bombed houses with whole walls missing

and people's beds and wardrobes sliding down towards the drop,

and their curtains torn and flapping in the wind. I didn't enjoy

this — it made me feel very insecure. Even now my house never

seems very secure to me, a crack in the wall makes me really anxious

that it might collapse.

There were raids in the night-time too. At first

we used to lie with our mother under the stairs listening to the

whine and crash of the bombs. She was very good at keeping calm

and used to pray The Lord's Prayer. Daddy, of course, was up the

church tower or out on the cliffs. We were only 20 miles from

Southampton where the docks were bombed, and planes returning

from the big Blitzes on Coventry for instance would off-load any

bombs they had left as they went above us over the coast. We learnt

to distinguish the difference between the engines of 'Ours' and

'Theirs' as we called the British and German planes. Soon we moved

all our beds into the front room downstairs.

A landmine nearly hits our house

One

night a landmine (much bigger than the usual bombs, and suspended

from a parachute), came floating down our road. It was about 3:35am

on 16th November 1940. The landmine was a tiny bit too high to

hit our house, and the houses of our friends, but it hit the school

just around the corner, where the French soldiers had stayed,

with an almighty bang. My mother was just coming into the room

with a fresh pillow for David who had been sick, and she saw the

whole window light up with an orange glow. She threw herself on

top of David and yelled at Daddy, (he was at home that night),

who tipped Cyril and me onto the floor, pulled our mattresses

on top of us and flung himself on top of that. One

night a landmine (much bigger than the usual bombs, and suspended

from a parachute), came floating down our road. It was about 3:35am

on 16th November 1940. The landmine was a tiny bit too high to

hit our house, and the houses of our friends, but it hit the school

just around the corner, where the French soldiers had stayed,

with an almighty bang. My mother was just coming into the room

with a fresh pillow for David who had been sick, and she saw the

whole window light up with an orange glow. She threw herself on

top of David and yelled at Daddy, (he was at home that night),

who tipped Cyril and me onto the floor, pulled our mattresses

on top of us and flung himself on top of that.

Once we felt safe to crawl out we found some of

our ceilings had fallen down and, extraordinarily, all the windows

facing towards the blast had been sucked out and the others had

been blown in. Daddy had to try to explain to us the effects of

the blast. Cyril got told off for running out to the breakfast

room to see the damage in his bare feet, as there was glass everywhere.

One young man who was disabled and worked in the

Bank with my father had been bombed out 7 times. His family would

always go out in the garden when there was a raid, it felt safer

to them. Some people dug air raid shelters in the garden, but

after the landmine we had a corrugated iron shelter called an

Anderson put in our front room. It was like an up-side-down U

and it was packed around with sandbags, and the windows in the

room had yellow sticky mesh put on them, and there were orange

and apple boxes filled with sand and stacked against the outside

of the walls. There were four bunks, one on top of the other on

each side of the Anderson where we children slept, and our parents

slept on the floor below. I remember it as being quite a big shelter,

but I have seen one over from the war recently and it's really

very small. I can't think how we all managed to squash into it.

* This recollection is drawn from WW2 People's War

- an online archive of wartime memories contributed by members

of the public and gathered by the BBC. The archive can be found

at www.bbc.co.uk/ww2peopleswar

|